In December last year, just before heading off for Christmas break, it was announced that the Winfarthing pendant had been voted the Art Fund’s acquisition of the year. Voters had been invited to choose from a shortlist of 10 works of art and objects that the Art Fund had helped UK museums and galleries to acquire in 2018. The list was comprised of artworks, both contemporary and historic, some by high profile artists like Greyson Perry and others, such as the Winfarthing Pendant, crafted by anonymous creators. To those of us who have had the privilege of being up close to the Winfarthing pendant, it is no surprise that this nationally-significant Anglo-Saxon treasure was top of the list.

The pendant as found

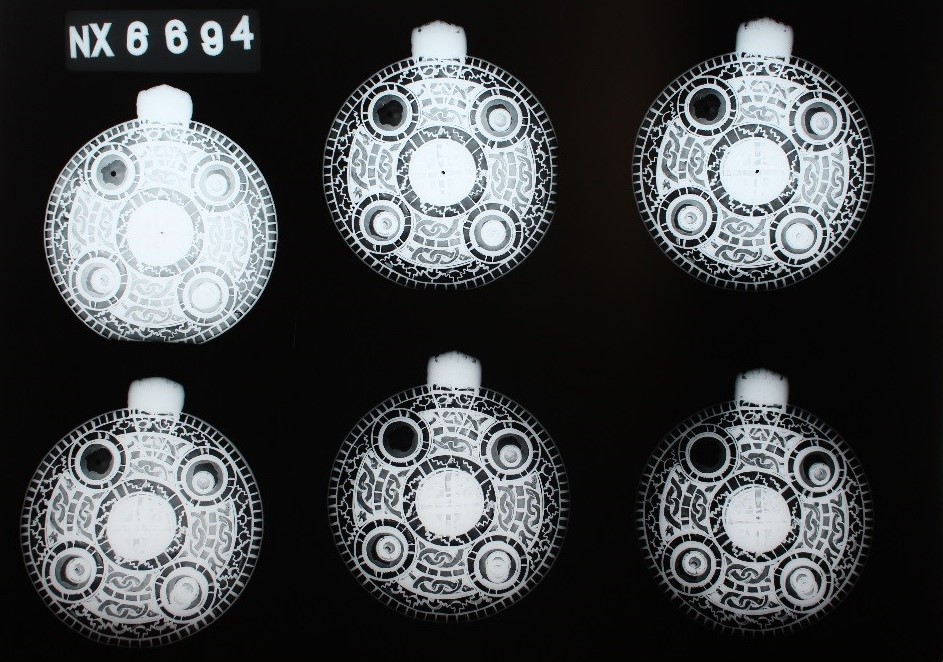

The pendant, found by a metal detectorist in a Norfolk field in 2015, was part of a 7th century grave assemblage that included a necklace made up of two gold beads, two pendants made from identical Merovingian coins and a gold cross pendant inlaid with delicate filigree wire. The assemblage was received by the Conservation Department upon excavation so that it could be packed appropriately for storage and transportation for its journey to the Treasure valuation committee. A radiograph was taken of the assemblage in our first stage of investigative work to assist in the valuation process. This helped ascertain the technology of the object which eventually assisted in the cleaning and conservation on purchase in the summer of 2018. The pendant is a gold disc inlayed with garnets, with a garnet inlayed central boss and four radiating bosses. On the reverse are corresponding garnet inlaid studs. The pendant was covered with hardened soil, sand and iron corrosion product. The grave goods had not been cleaned or over handled prior to conservation treatment. Initial assessment of the pendant revealed how crucial this minimal initial intervention had been, as many of the garnets, which sit in individual cells often measuring less than 1x1 mm, were only held in place by dry and sandy soil from which the pendant was excavated. This was also the case for the central boss, which sat loosely on the surface of the pendant. Loss of many of the garnets would surely have been the case if cleaning had been attempted immediately on discovery.

Object conservator Jonathan Clark ACR working under high magnification and using a further digital microscope to aid the assessment and stabilisation.

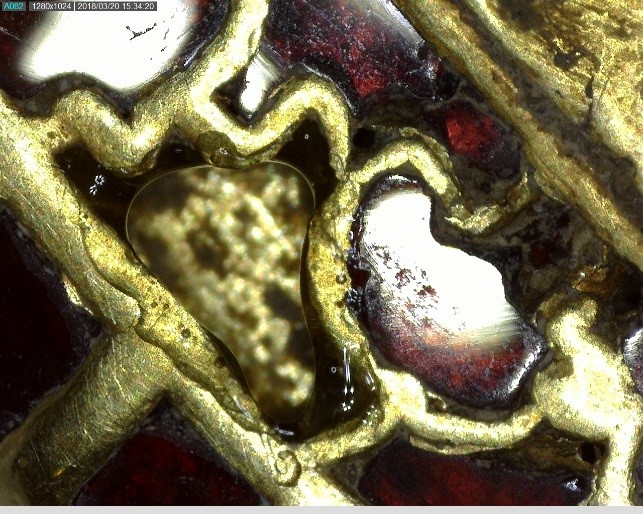

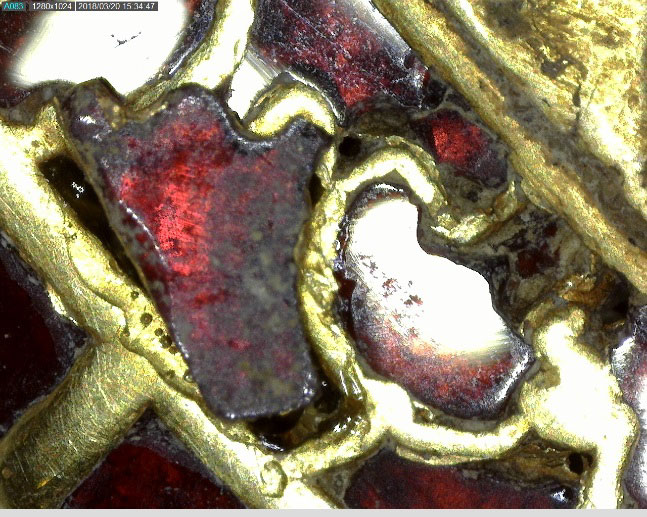

Once the pendant had been acquired and returned to the conservation lab, it was cleaned cell by cell under the microscope, using very fine tools. Small quantities of alcohol were introduced using brushes and purified cotton wool swabs to soften or remove residues of soil. Many of the loose garnets, some broken, had ‘collapsed’ into their cell, which had then filled with soil. This resulted in the waffled gold foil under the garnet being either loose or crushed. In order to re-secure the garnet, the garnet and the gold foil had to be lifted out, cleaned and replaced. Some garnets had foil wrapped around their underside, pinched around the edges, probably to help wedge the garnet in its cell. This accentuates the importance of working under high magnification, understanding the technology of the object you are working on, and of course, the importance of a conservator’s steady and skilful hand! The garnets were painstakingly adhered in situ. Once the obverse was stabilised, the object could be turned over and the reverse worked on.